BY @ANAGA SIVARAMAKRISHNAN | 7 MIN READ | PUBLISHED ON 28.2.2024

Trusted information and trusted sources in health

Navigating the landscape of health information overload and health literacy

The development sector works to improve the well-being and quality of life of communities, promotes environmental sustainability and fosters public policy and advocacy. The process of development follows the lives of people, their problems and designing solutions for these complex problems. Coming from a development background, I recognise the importance of discussions and dialogues in the sector as the preliminary phases of solving problems greatly involve a deep dive into understanding the problem through a series of discussions and consultations. These interactions could be with any stakeholders of the society - community, institutions or government. However, never did I imagine that a technology like AI could be an integral part of these human conversations and hold the capability to reimagine the process of development.

Health literacy and information overload

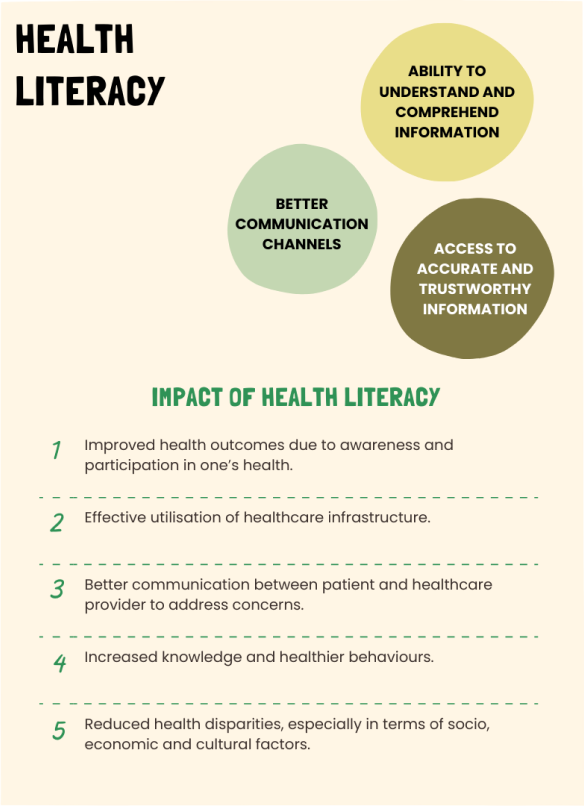

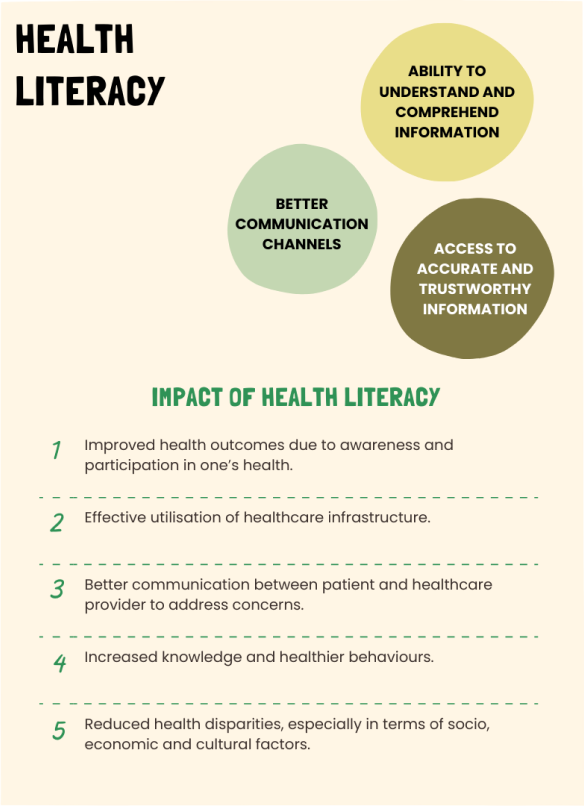

An individual's ability to obtain, process, and understand basic health information and services in order to

make informed decisions about their health is defined as health literacy. It includes a

wide range of skills

and awareness to navigate healthcare systems, understand medical terminology, and interpret health

information. It is very essential to enable people to understand their medical conditions, engage with

healthcare providers and make informed decisions about their health.

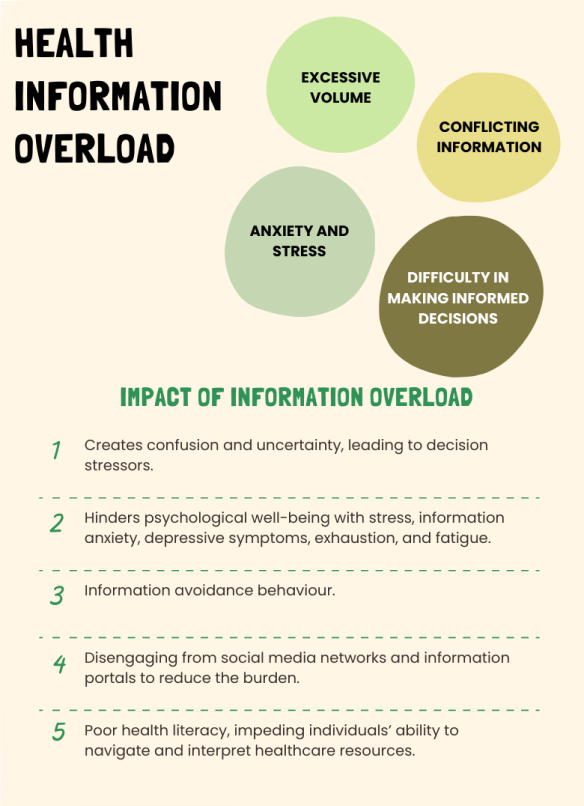

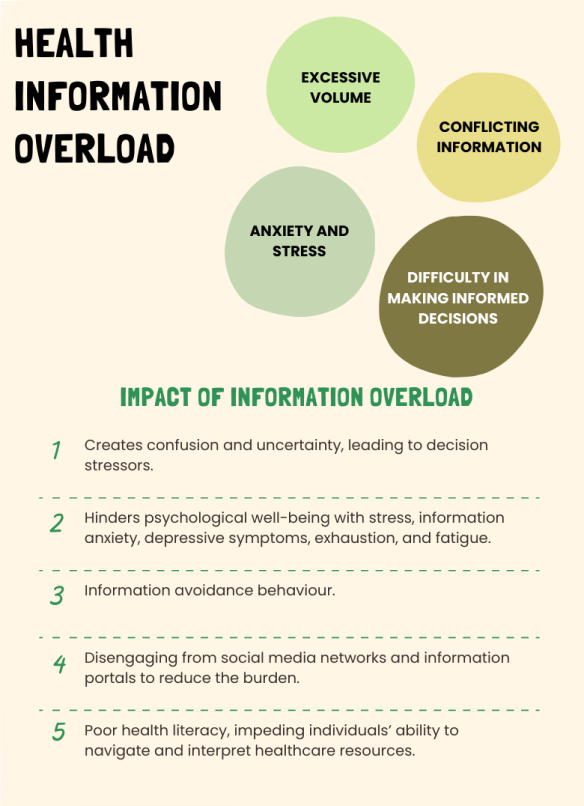

Health information overload, on the other hand, is an excessive amount of information individuals are exposed to. This can overwhelm individuals and make it difficult to understand and make decisions for their health. There has been a steep rise in health information overload with increasing usage of internet and digital technologies, making it easy to access health information from different sources, with varying degrees of accuracy and credibility. Many times, a simple online search can lead down a rabbit hole of contradictory information, leading to confusion, stress and inability to make informed decisions.

The fine line between poor health literacy and unauthenticated health information overload can contribute to health anxiety, where anxious individuals are not only impacted psychologically on an individual level but also contribute to spreading health rumours. The spreading of incorrect information results in dangerous and negative consequences. When tracing the relationship between reducing health information overload and improving health literacy, we can observe that trusted, credible information and sources can enhance this.

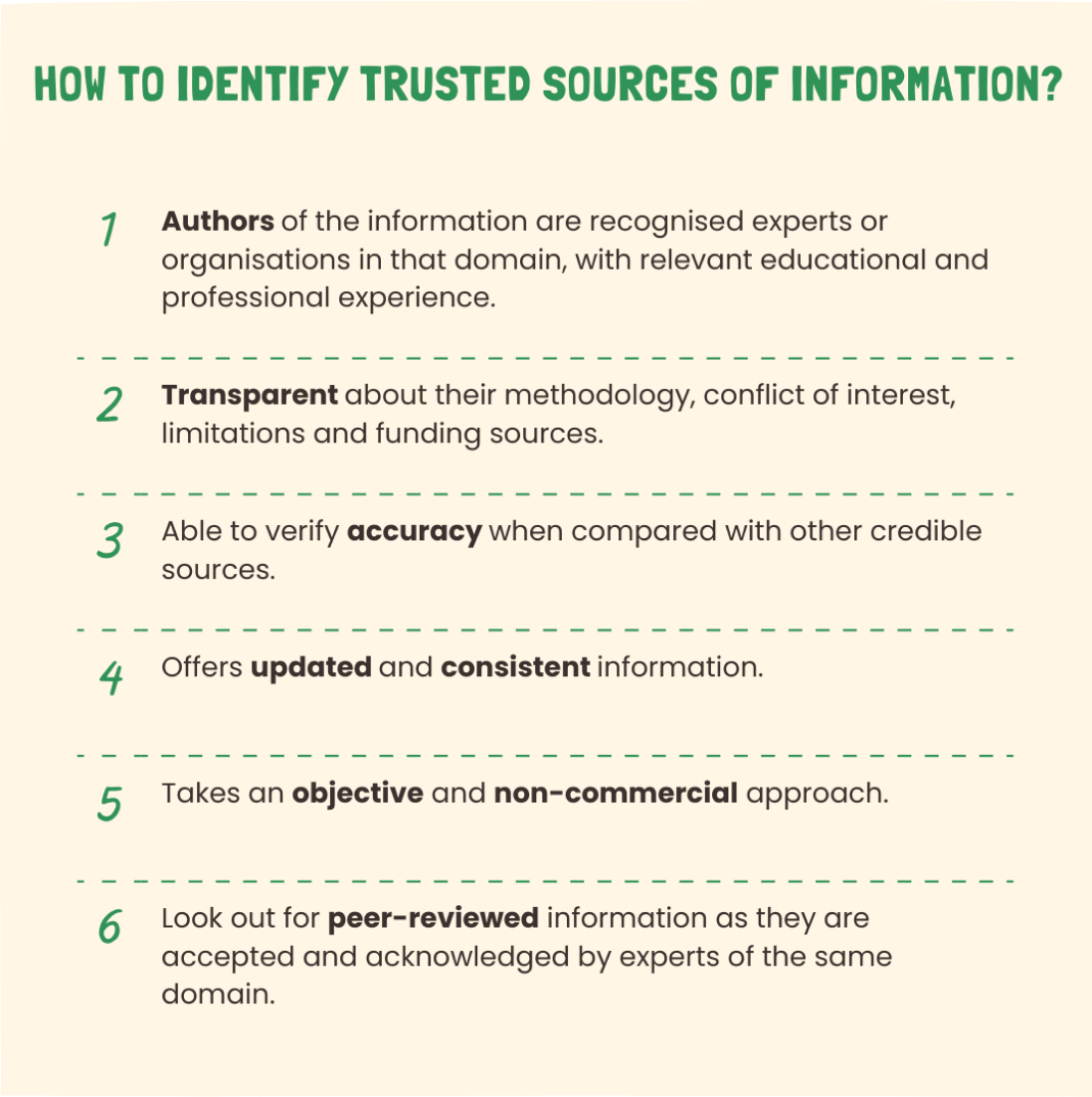

Trusted sources are those that meet the criteria of credibility, clarity and transparency.

Information from healthcare professionals, health organisations, government, academic and research institutes, and regulatory bodies are well regarded and trusted for health.

Trusted sources in health

Trusted health information, when made easy to access, understand, apply and appraise for informed decision

making, improves health literacy. Health information can be filled with jargon and tough to understand. So,

how can health information be accurate, relevant and understandable?

Different stakeholders in healthcare can also play a role in promoting trusted information to improve health literacy. Medical practitioners have the responsibility to ensure information on health is communicated clearly and effectively. Offering trusted and credible information, they need to tailor it to the patient's specific needs. This can be done by using simple language, visual aids and different communication techniques. Information can be easier to grasp with varied and interesting representations like graphs, infographics, case studies and stories, grounded in local and cultural context.

Patients have to actively seek out trusted sources to access and understand health information. This way, they are informed, updated, course correct when required and participate in their healthcare.

It is inspiring to witness how simple conversations in passionate organisations like SELCO Foundation, ProjectECHO and Catalysts Group can be a game changer when leveraged with co-creation and collective wisdom across departments, geographies and networks!

Systematic reviews by researchers and policy advocates is grounded in conducting rigorous research, analysing evidence on various health topics to provide evidence-based recommendations. They can not only guide patients and practitioners to trusted health information, but also identify and address research gaps in healthcare.

Well curated information from trusted sources can help to build a trusted repository on healthcare. It can be used as the foundation to raise awareness and provide interventions, specifically targeting populations with low health literacy. With more and more people turning towards television, internet platforms and social media for information consumption, health professionals and experts can focus on providing relevant, accurate information. Furthermore, online repositories can encourage eHealth literacy. This curation of trustworthy sources can aid to improve people’s capabilities to evaluate the quality and credibility of health information and their sources, leading to better health lifestyles and addressing healthcare disparities.

Trust, an essential when it comes to information and sources of information, is a concept Apurva.ai is grounded in. It is one of Apurva’s core values. Building a platform of collective wisdom will be more relevant and effective with trusted sources of information, where the ecosystem can readily lean on these layers of knowledge curated.

How important is trust and credibility of information important to you?

References:

- Chen, X., Hay, J. L., Waters, E. A., Kiviniemi, M. T., Biddle, C., Schofield, E., ... & Orom, H. (2018). Health literacy and use and trust in health information. Journal of health communication, 23(8), 724-734.. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10810730.2018.1511658

- Crook, B., Stephens, K. K., Pastorek, A. E., Mackert, M., & Donovan, E. E. (2016). Sharing health information and influencing behavioral intentions: The role of health literacy, information overload, and the Internet in the diffusion of healthy heart information. Health communication, 31(1), 60-71.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25668744/ .

- Ghaddar, S. F., Valerio, M. A., Garcia, C. M., & Hansen, L. (2012). Adolescent health literacy: the importance of credible sources for online health information. Journal of school health, 82(1), 28-36. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22142172/#:~:text=Conclusion%3A%20Exposure%20to%20a%20credible,approach%20for%20promoting%20health%20literacy

- Hong, H., & Kim, H. J. (2020). Antecedents and consequences of information overload in the COVID-19 pandemic. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(24), 9305. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/24/9305

- Khaleel, I., Wimmer, B. C., Peterson, G. M., Zaidi, S. T. R., Roehrer, E., Cummings, E., & Lee, K. (2019). Health information overload among health consumers: A scoping review. Patient education and counseling, 103(1), 15-32. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0738399119303246.

- Klerings, I., Weinhandl, A. S., & Thaler, K. J. (2015). Information overload in healthcare: too much of a good thing?. Zeitschrift für Evidenz, Fortbildung und Qualität im Gesundheitswesen, 109(4-5), 285-290.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/26354128/.

- Levin-Zamir, D., & Bertschi, I. (2018). Media health literacy, eHealth literacy, and the role of the social environment in context. International journal of environmental research and public health, 15(8), 1643. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/15/8/1643.

- Oh, H. J., & Lee, H. (2019). When do people verify and share health rumors on social media? The effects of message importance, health anxiety, and health literacy. Journal of health communication, 24(11), 837-847.https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/10810730.2019.1677824.

- Rathore, F. A., & Farooq, F. (2020). Information overload and infodemic in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Pak Med Assoc, 70(5), S162-S165. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Farooq-Rathore/publication/341283222_Information_Overload_and_Infodemic_in_the_COVID-19_Pandemic/links/5ec4d8cc458515626cb84e1c/Information-Overload-and-Infodemic-in-the-COVID-19-Pandemic.pdf.

- Soroya, S. H., Farooq, A., Mahmood, K., Isoaho, J., & Zara, S. E. (2021). From information seeking to information avoidance: Understanding the health information behavior during a global health crisis. Information processing & management, 58(2), 102440.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S030645732030933X.

- Sentell, T., Vamos, S., & Okan, O. (2020). Interdisciplinary perspectives on health literacy research around the world: more important than ever in a time of COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(9), 3010. https://www.mdpi.com/1660-4601/17/9/3010.